Crypto Self-Sovereignty in 2026: What It Really Means (And Where It Breaks) January, 2026

Self-sovereignty in crypto goes far beyond holding your own keys. This guide explains what real control looks like in 2026, where most users are still dependent on third parties, and how to reduce those risks without sacrificing usability.

Written by Nikolas Sargeant

Written by Nikolas Sargeant

In 2026, owning crypto is normal. Real control is not.

Most people assume self-sovereignty just means “not your keys, not your coins.” That’s part of it, but it’s not the full picture. You can hold your own keys and still be dependent on a single wallet app, a single infrastructure provider, or a single company’s servers to actually use your assets. When that dependency fails, your “control” can disappear fast.

This is why self-sovereignty isn’t a product you buy, it’s a setup you build. It’s about resilience: being able to access funds, approve transactions, and recover your wallet even when something goes wrong, whether that’s an outage, an interface going offline, a policy change, or simply a lost device.

In this guide, we’ll define what crypto self-sovereignty really means in 2026, show where it commonly breaks in the real world, and lay out practical ways to reduce reliance on third parties without turning your life into an IT project.

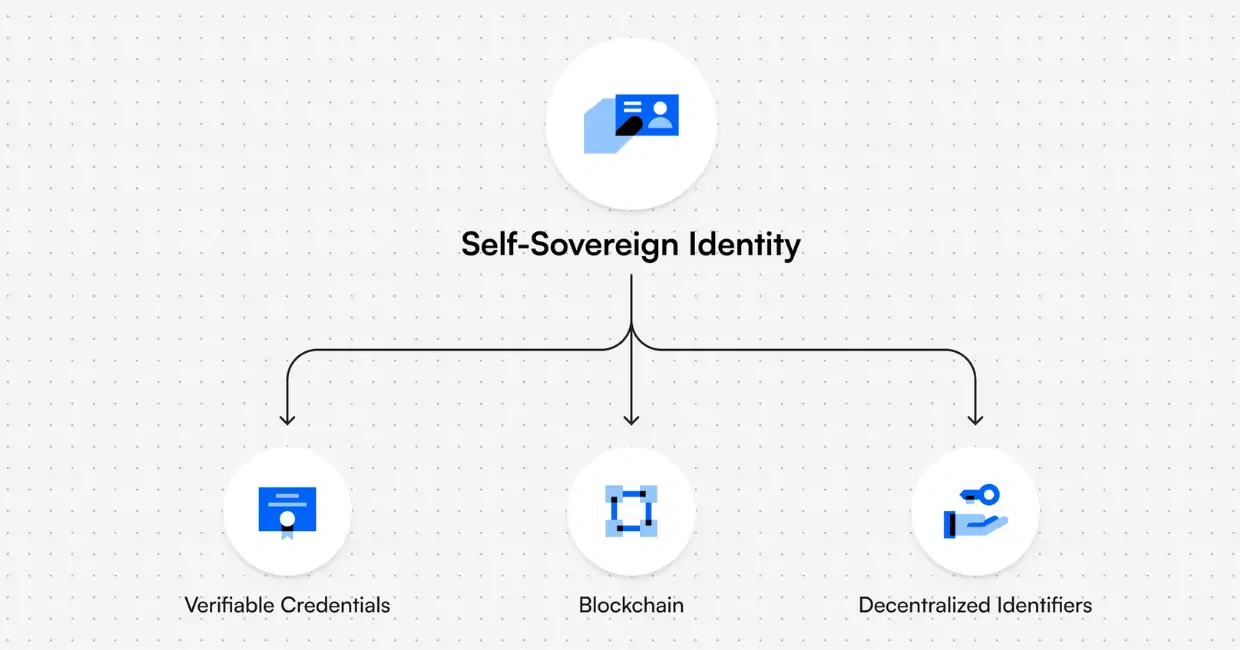

What Self-Sovereignty Actually Means in Crypto

Self-sovereignty in crypto is not a vibe, and it’s not a political statement. It’s a practical question:

Can you still control and move your assets if one company, one app, or one service disappears?

To make that real, it helps to think of self-sovereignty as control across four layers. Most users focus on the first one and ignore the other three.

The 4 layers of crypto self-sovereignty

- Keys: Who can approve transactions and move funds. If you don’t control the keys, you don’t control the assets.

- Access: How you connect to the network. Many “non-custodial” wallets still route through a single provider for blockchain access.

- Execution: How transactions get broadcast and confirmed. If your only transaction path relies on one interface, you can be blocked even with valid keys.

- Recovery: What happens when you lose your device, your app breaks, or your backups fail. Recovery is where most self-custody setups silently collapse.

What self-sovereignty is not

- It’s not the same as self-custody. Self-custody is key ownership. Self-sovereignty includes everything you depend on to actually use those keys.

- It’s not “decentralization” in the abstract. A blockchain can be decentralized while most users access it through centralized bottlenecks.

- It’s not “no regulation.” Rules may shape exchanges and payment rails, but sovereignty failures usually come from convenience-driven reliance on intermediaries.

A real-world example: the wallet works, but you can’t send

Here’s a common 2026 failure mode: your wallet is non-custodial and you have your seed phrase, but the app can’t load balances or send transactions because the wallet’s default network provider is degraded or offline. The blockchain is still producing blocks, but your access path is broken.

That’s the sovereignty gap in one sentence: you own the keys, but you don’t control the route.

From here, the goal isn’t perfection. It’s reducing single points of failure so you can still act when something breaks.

Self-Custody vs Self-Sovereignty: The Critical Difference

Self-custody is often treated as the finish line. In reality, it’s just the starting point.

When people say they “control their crypto,” they usually mean one thing: they hold their own private keys. That matters, but key ownership alone does not guarantee independence, resilience, or access when conditions change.

Self-custody explained

Self-custody means you control the private keys that authorize transactions. No exchange, custodian, or third party can move your funds without your approval. This protects you from account freezes, withdrawal limits, and platform insolvency.

However, self-custody says nothing about how you connect to the blockchain, which services you rely on to broadcast transactions, or how you recover access if something breaks.

What self-sovereignty adds

Self-sovereignty looks beyond the keys and asks whether your entire setup can survive failure. It includes:

- Whether you can access the network through more than one provider

- Whether you can use your keys without a single wallet interface

- Whether you have a recovery path that does not depend on customer support

Real-world example: hardware wallet, single point of failure

Consider a user with a hardware wallet. They hold their keys offline and never leave funds on an exchange. On paper, this looks like ideal self-custody.

In practice, many hardware wallet users rely on a single companion app to view balances, sign transactions, and connect to the network. If that software becomes unavailable, restricted, or incompatible with their operating system, the user may still own the keys but lack an easy way to use them.

This is where self-sovereignty diverges from self-custody. One protects ownership. The other protects usability under stress.

In 2026, the difference matters more than ever because most crypto failures are not hacks. They are access failures.

The Illusion of Control: Hidden Dependencies Most Users Ignore

Most crypto users believe they are independent because they are not using an exchange. In reality, many self-custody setups still rely on a fragile stack of services that users rarely think about until something breaks.

These dependencies are not obvious because they sit below the wallet interface. Everything appears decentralized on the surface, while access is quietly funneled through a few centralized choke points.

RPC providers: the invisible gatekeepers

When you open a wallet and see your balance, your wallet is usually querying a remote node operated by an RPC provider. If that provider is slow, rate-limited, or offline, your wallet may fail to load or send transactions even though the blockchain itself is functioning normally.

For most users, this means one thing: their ability to transact depends on a service they didn’t choose and often don’t even know exists.

Wallet frontends and hosted interfaces

Non-custodial does not mean self-hosted. Many wallets and decentralized apps rely on hosted frontends that can be updated, restricted, or taken offline without warning.

If your only way to interact with a protocol is through a single website or app, that interface becomes a control point. The smart contracts may still exist on-chain, but access to them is effectively gated.

Cloud backups and convenience recovery

Modern wallets increasingly offer cloud-based recovery to reduce user error. While this improves usability, it introduces a new dependency: access to an external account, service, or provider.

If that account is locked, compromised, or unavailable, recovery may fail even if you technically still “own” your wallet.

App stores, operating systems, and updates

Mobile wallets depend on app stores, operating system updates, and device compatibility. A forced update, region restriction, or device failure can instantly cut off access to funds.

This is not a theoretical risk. In 2026, many users experience temporary loss of access not because crypto failed, but because their access layer did.

The core problem: single points of failure

Each of these dependencies is manageable on its own. The risk appears when they stack.

If your keys, wallet interface, network access, and recovery path all depend on one company or service, you do not have sovereignty. You have permissioned self-custody.

Understanding where these hidden dependencies live is the first step toward reducing them.

What Happens When Things Break: Real-World Failure Scenarios

Most losses of control in crypto do not come from hacks, scams, or stolen keys. They come from ordinary failures in the tools and services people rely on every day.

These scenarios are increasingly common in 2026, not because blockchains are unstable, but because access to them is layered through complex infrastructure.

Scenario 1: the network is live, but you can’t transact

The blockchain is producing blocks normally. Explorers show activity. Other users are sending transactions. Your wallet, however, can’t load balances or broadcast anything.

This usually points to an access-layer failure: an overloaded or degraded RPC provider, a wallet backend outage, or rate limits kicking in during periods of high activity. From the user’s perspective, crypto feels “down,” even though nothing is wrong on-chain.

If you rely on a single wallet and a single network provider, you have no immediate way around this.

Scenario 2: the interface disappears

You open a decentralized app you’ve used for months, only to find the site offline or inaccessible. The smart contracts still exist, and your funds are still there, but the interface you depended on is gone.

Advanced users may interact directly with contracts or use alternative frontends. Most users cannot. For them, the loss of the interface is equivalent to losing access.

Scenario 3: device loss and recovery failure

Your phone is lost, damaged, or reset. You reinstall your wallet, but recovery depends on a cloud backup, account login, or recovery service that is now unavailable.

Technically, your assets were never taken. Practically, you are locked out.

Why these failures matter

None of these scenarios involve malicious actors. They are normal operational failures that occur in any software ecosystem.

Self-sovereignty is about planning for these moments. If your setup only works when everything else works, your control exists on borrowed time.

Regulation in 2026: What It Affects and What It Doesn’t

Regulation is often blamed when users lose access to crypto services, but in most cases, the issue is not regulation itself. It’s how users choose to access the ecosystem.

By 2026, regulatory frameworks are clearer than they were a few years ago. The important detail is that most rules apply to companies, not to blockchains or self-hosted wallets.

What regulation actually affects

- Centralized exchanges and custodians

- Fiat on-ramps and off-ramps

- Payment processors and settlement providers

- Custodial wallets and managed accounts

When access is restricted due to compliance, it usually happens at these layers. Accounts may be frozen, transactions delayed, or services suspended, even though the underlying blockchain remains fully operational.

What regulation does not directly control

- Self-hosted wallets where users control their keys

- Peer-to-peer on-chain transactions

- Open-source smart contracts already deployed on-chain

This distinction matters because many users interpret access loss as confiscation. In reality, assets are rarely seized. More often, the access point is closed.

The real sovereignty risk

The largest threat to sovereignty in a regulated environment is not the law. It’s concentration.

If all of your access to crypto flows through one exchange, one app, or one provider that must comply with enforcement actions, your control is fragile by design.

Regulation shapes the edges of the system. Dependency determines how exposed you are to it.

Patterns Observed in 2024–2026

Between 2024 and 2026, several high-profile incidents made one thing clear: when users lost access to crypto, the blockchain was almost never the point of failure. Control broke higher up the stack.

Across different networks, wallets, and regions, the same failure patterns repeated.

Pattern 1: infrastructure stress breaks wallets before blockchains

In multiple periods of heavy network activity between 2024 and 2025, users on major EVM-compatible networks reported wallet balances failing to load and transactions timing out, even though blocks were being produced normally.

In these incidents, the bottleneck was not consensus. It was RPC congestion and indexing backlogs. Wallets relying on default infrastructure providers became partially unusable, while users who had configured alternative endpoints were still able to broadcast transactions manually.

This created a visible divide: technically sovereign users experienced inconvenience, while convenience-only users experienced total loss of access.

Pattern 2: frontend outages lock users out of on-chain assets

Several decentralized application frontends went offline temporarily during this period due to hosting failures, DNS issues, or infrastructure misconfigurations. In each case, the underlying smart contracts remained live and funds remained on-chain.

However, users who only knew how to interact with those protocols through a single website or app were unable to manage positions, withdraw funds, or exit exposure.

Advanced users accessed contracts through alternative interfaces or direct calls. Most users could not. For them, a frontend outage functioned exactly like asset loss.

Pattern 3: wallet recovery failures outnumber security breaches

Support forums and post-mortem reports from 2024 onward showed that permanent access loss was more often caused by recovery failures than by hacks.

Common real-world cases included lost or upgraded phones where cloud backups failed to restore wallet state, wallet updates that corrupted local data, and seed phrases stored in locations that were inaccessible when urgently needed.

In these scenarios, there was no attacker and no protocol bug. The blockchain behaved correctly. The failure was entirely in the recovery design assumed by the user.

Pattern 4: regulation constrains services, not protocols

Regulatory enforcement actions during this period largely targeted centralized exchanges, custodians, and payment processors. Users experienced frozen accounts, delayed withdrawals, and sudden service exits in certain jurisdictions.

On-chain activity continued uninterrupted throughout these events. Users who self-custodied and maintained multiple access paths were able to move funds independently, while those whose entire setup depended on a single regulated intermediary lost practical control overnight.

The protocol layer remained neutral. Access concentration determined who felt the impact.

The common thread

Across all these examples, control failed at the edges, not at the core.

Users who diversified wallets, access routes, and recovery methods experienced friction. Users who centralized everything into one app, one provider, or one service experienced loss of control.

Between 2024 and 2026, this pattern repeated often enough to become a rule rather than an exception.

The Self-Sovereignty Reality Check

By this point, one thing should be clear: self-sovereignty is not a switch you flip. It’s a spectrum.

You do not need to run your own node, audit smart contracts, or abandon modern wallets to be more sovereign. What matters is whether your setup can tolerate failure without turning inconvenience into loss of control.

The easiest way to assess that is to ask a few uncomfortable but practical questions.

- Can you move your funds without relying on a single company, app, or interface?

- Can you still transact if your primary wallet app goes offline?

- Do you have a recovery method that does not depend on customer support or cloud access?

- Could someone you trust access your assets if something happened to you?

If any of these questions give you pause, that doesn’t mean your setup is broken. It means you’ve identified a dependency you can now choose to reduce.

That awareness alone is already a meaningful step toward sovereignty.

Conclusion: Sovereignty Is About Resilience, Not Isolation

In 2026, crypto self-sovereignty is less about rejecting systems and more about understanding them.

Blockchains have proven remarkably resilient. What continues to fail are the layers built on top of them: interfaces, infrastructure, recovery flows, and convenience abstractions. When users lose control, it is almost always because too much trust was concentrated in one place.

The goal is not to eliminate every dependency. That is neither realistic nor necessary. The goal is to avoid brittle setups where a single failure turns ownership into inaccessibility.

Small changes matter. A second wallet. A tested recovery path. An alternative access route. Each one reduces the distance between owning crypto and actually controlling it.

Self-sovereignty is not about doing everything yourself. It’s about making sure that when something breaks, you still can.

Comments

Log in to post a comment

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!